The Spiral and the Flywheel

We all have gaps in life.

You may want to exercise more, eat better, earn more, find a path through a forest of projects, or grow your fledgling start-up.

Gaps are good—we need challenges in life to get us out of bed and give us purpose. Gaps at work give us opportunities to learn, grow our social standing, and increase our economic value.

And gaps lead to two choices.

The first is to get focused, take action, and close the gap. That’s what we all hope for—the positive experience that motivates us to achieve more. “Momentum fuels motivation.” Fried and Hansson write in Rework.

The other path is the downward spiral.

The downward spiral

Just like a spinning top that eventually stops, the downward spiral is the path to a dead end.

Recently, in a workshop I was leading, a senior executive of a large company shared her struggles to protect time on her calendar for critical thinking and decision-making. Whatever plan she built for the week is quickly chipped away as her direct reports, clients, and suppliers fill her inbox with requests for meetings or seeking her advice. “I carefully plan my day,” she complained “and then all hell breaks loose and everyone wants my time.” And she added, “It happens all the time.”

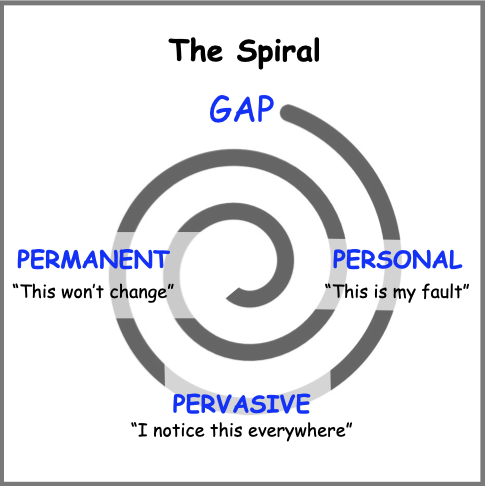

The downward spiral starts when you own the problem. “It’s my fault.” You think - as if there is a fault in your wiring. I do this when I make a mistake in front of an audience - like starting to share a quote and then realizing I’ve forgotten the author’s name. Or, when I get emotionally triggered and in the race to say something my mouth runs ahead of my brain.

Next, I start to notice the problem everywhere. “I’m always doing this!”, I think, or “They’re always doing this.” Like a bicycle tire, we pump up the problem and make it bigger.

Finally, we conclude the problem is real, big, and not going away. “That’s just the way I am”, we think. “I’m always running late”, or “There’s never enough time”, or “That’s just the way they are.”

Psychologist, Martin Seligman describes these three stages as “learned helplessness” with the tidy titles of Personal (it’s my fault), Pervasive (it’s everywhere), and Permanent (it’s not going away anytime soon). “Learned helplessness is the giving-up reaction,” he writes, “the quitting response that follows from the belief that whatever you do doesn't matter.”

Like a Rube Goldberg machine, insert any problem into the downward spiral - eating, exercise, sleep, sales, conflict, writing, etc. - and it will predictably spit out the same result. Nothing changes.

But, it gets worse—when we repeatedly feed the downward spiral we also fuel the rivers in our mind.

Rivers in our mind

As a kid, I grew up kayaking wild rivers. When you’re strapped into a sliver of fiberglass with nothing but a paddle for steering you quickly learn that other than small changes in direction, you are going with the flow.

Our mind is like a massive complex of rivers. Each stream is gradually carved from a single idea into a pattern of thinking over years of programming. We all have streams for health - should I eat this, or not? - dealing with (or not) conflict, planning, decision making, and, of course, self-perception - what we think about this amazingly complicated person we have become.

Just like a river, every time you think, “I’m always doing this!” that stream gets carved just a little deeper. Keep repeating the same thought and pretty soon it becomes your reality.

Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb famously simplified this highly complex phenomenon into one tidy formula “Neurons that fire together wire together.”

And because your mind is a glutton for resources - the brain constitutes about 2% of our body weight, but consumes some 20% of body energy - it takes shortcuts, or what author and filmmaker, Robert Fritz coined as the path of least resistance.

If someone cuts you off in traffic, instead of rationally considering whether they simply didn’t see you, or maybe they just got bad news about a family member, we open the dam on our conflict stream and get flooded with feelings of anger.

The good news is there is another, more resourceful approach - the flywheel.

The Flywheel

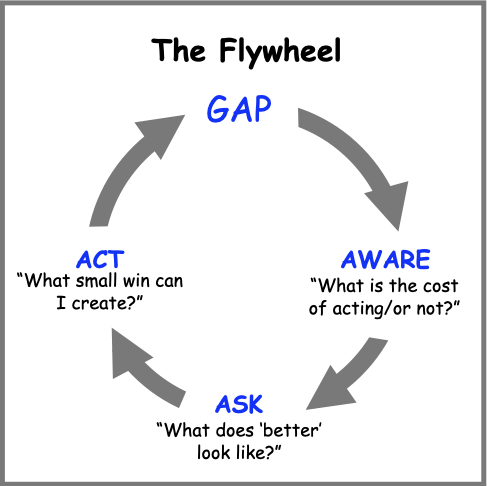

The flywheel is like a Swiss army knife of progress—it’s adaptable for any situation, incredibly effective, and always available.

And it starts with a question.

Aware

Life will always deliver a full menu of challenges. You can’t eat them all so you have to decide if this is a battle worth fighting. The question I ask is: “What is the cost?”

What is the cost if I choose to tackle this? Will this chew up a lot of my emotional reserves or derail me from the path I was on?

What is the cost if don’t deal with this? After all, there are lots of problems, like bad service at a restaurant, or a team member missing a deadline I can choose to ignore or deal with later.

When you approach gaps in life with curiosity, it’s like kicking your heel at the side of the river and opening a tiny new stream. Kick often enough and the tiny stream gains volume. Repeat this new way of thinking often enough and your life changes.

Ask

If I’ve made the decision to tackle a problem, I need to next ask: what does ‘better’ look like?

Transforming a problem - especially a well-entrenched one - into a perfect solution isn’t always possible. But, making strides towards ‘better’ often is.

For the executive who is constantly interrupted, ‘better’ is time blocking. By scheduling half-hour or longer time blocks, she protects time for deep work. Just like a meeting, the blocked time is in her calendar, visible to anyone, and respected.

With a view of what ‘better’ looks like, it’s time to zoom in on a small win.

Act

A small win is any step forward that gets you closer to closing your gap. By asking "What small win can I can create right now?" I move from worry and stress into a proactive, creative state where I am looking for some small - even imperfect - effect I can make in just a few minutes.

On my Flight Plan this week was the task of setting up a meeting with a volunteer team I’m leading. The topics are complicated the decisions are difficult and I wasn’t even sure who needed to be in the meeting. I needed a small win, so I quickly drafted the agenda. I still need to book the meeting and send the invitations, but now the flywheel is turning and I have progress.

If I forget about a scheduled meeting I can either beat myself up (downward spiral) or create a small win (flywheel) by sending a quick apology email and asking to reschedule.

If I miss a workout at the gym or a morning walk with my dog I can either dive into a pool of self-pity full of negative thoughts (downward spiral) or create a small win (flywheel) by going for a short walk later in the day. That’s progress.

Progress

Life is full of problems. It’s up to us what we do with them.

We can either stoke the fires of helplessness, convincing ourselves the problem is permanent or throw a bucket full of curiosity on it and seek a small win.

Start by being aware of the gaps in your work, health, relationships, or planning. We can’t win every battle, so choose your battles carefully. Next, ask yourself what would ‘better’ - not perfect - look like. Remember the goal is small wins in the run toward creating progress, not another big goal that could drop dead at the start line.

And then take action.

It might be 10 minutes cleaning your desk, booking a long overdue meeting, finding a new walking route for some lunchtime exercise, or turning annoying app notifications off.

Progress happens when the flywheel of change has momentum. To get the flywheel spinning give it a nudge. I call that a small win.

If this was helpful, you might also like my pick of related posts:

How to get started on your goals with small wins

Small Wins - Why Little Steps are the Path to Big Rewards

Keynotes and workshops by Hugh Culver